How Lloyd Best Used the Media to Affect Change

It seems safe to conclude that the entity, or entities, called the media have been afflicted by such low self-esteem as not to regard themselves (ourselves) as any “instrument”, or “agents”, decisive for attaining such grandly historic objectives as “decolonisation” and “localisation”. I venture to imagine that my own experience will be borne out by the testimony of colleagues.

Which is that the all-consuming goal of media work has been getting the stories done, and getting the paper out, (or getting the newscast done), making best possible use of the human and other resources on hand, and doing so on the deadline preordained by business and production disciplines. But the fates would decide differently. Lloyd Best would come calling, through the then literally open doors of the media houses.

A man of his rank and repute was seeing in the media (then principally daily newspapers) a critical factor in a mission of transformation. It’s here defined as “decolonisation and “localization”. And labels would be put on it deriving from where people stood. In an anecdote he shared with me (I can’t recall seeing this episode documented anywhere), Best on visiting Trinidad in 1965, had published an article in the Guardian. On the basis of which he found himself summoned before the notorious Mbanefo Commission on “subversive activities”.

Now, this was serious, even risky. The government’s appointment of the Mbanefo Commission gave effect to concern with “Communist subversion” in T&T. As a measure of this governing concern, CLR James, on arrival here to cover a cricket series, was put under house arrest in Barataria. As far as I know (that was “before my time”, as they say), Best returned unscathed to wherever in the world in the world he then operated.

But he would be back to stay, and by then the Express was in operation, in daily competition with the Guardian. The two dailies constituted what came to be called the “conventional media”. But around the turn of the 1960s decade and into the 1970s, multiple publishing titles and efforts of greater and lesser presentability had come on the scene.

MOKO, Vanguard, the New Beginning and, eventually, Liberation, could afford newsprint. But the hustle to get into any kind of print led to the emergence, under the NJAC publishing umbrella alone, of East Dry River Speaks, Belmont United Front, The Black Woman, Black Expression, The Grassroots (identified with Carenage, Diego Martin, Point Cumana and Petit Valley). That’s just a partial list of the items pressed on Port of Spain passersby or stuck under the doors of media houses.

All together, they exemplified a searching for more media more diversified in direction and approach than the “conventional”. In 1970, too, the BOMB, joint effort of Bhadase Sagan Maharaj and Patrick Chookolingo, detonated a promise of an unending sequence of media titles.

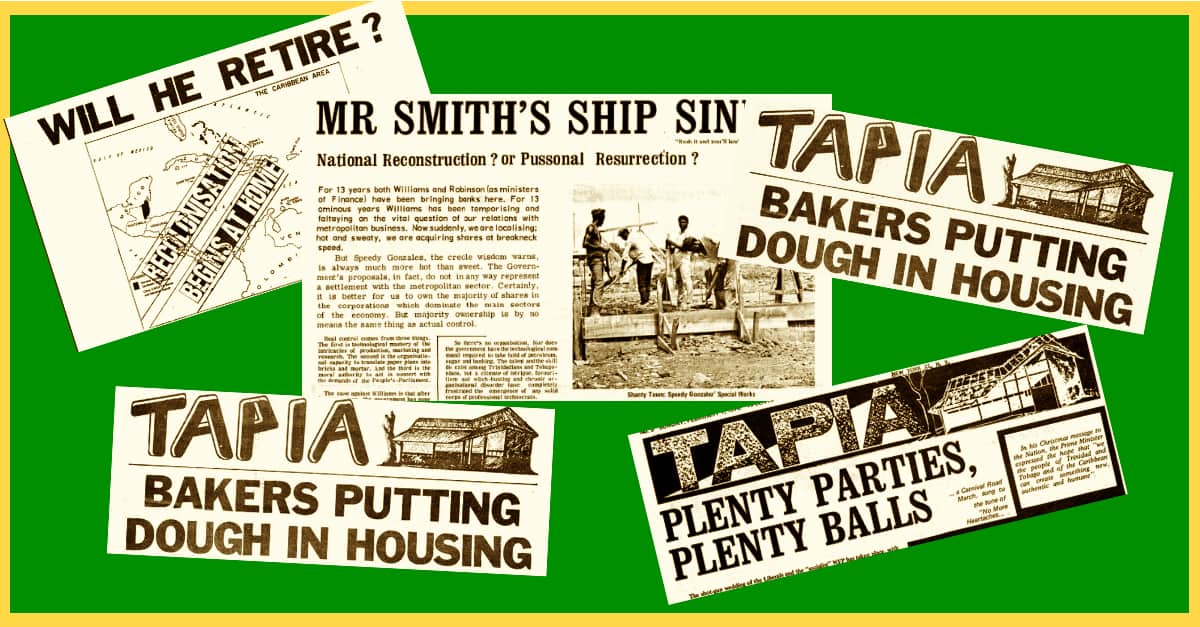

By then, the TAPIA flag had been raised, identified with the leadership of Lloyd Best, byline of lead stories in the first three issues. It was an age of bumper media input and output. TAPIA, printed on white bond paper, at first went for small headlines, presenting its content in disciplined design that gave emphasis to material both long and deep. The paper took advertising, suggesting a purposeful intent to gain means for a self-sustaining livelihood. It met the need for identifiable style rules: the “By” was dropped from bylines, a practice now common in all T&T print media. The editorial was tagged “The Movement”.

Evidently, the going got tough. Between September 1969 and April 1972, just 25 issues of TAPIA came out. Early on, an editorial noted the aim to find “a sufficient diversity of people who can write pointedly about the here and now”. From inside and around the Tapia organisation, such people evidently kept coming forward. In lead articles, the Lloyd Best byline dominated, but shortly the names, Adrian Espinet and Denis Solomon appeared above such leads.

In what today would be called investigative journalism, an eye catching report, “STEAL MILL—ANY PRICE”, led the paper. An expose of a questionable government-approved project hustled by a foreigner, it was written by Emile Elias. One month later, he followed up under the headline “Coitus Interruptus”. Elias reported: “The Steal Mill, largely due to TAPIA, is dead.”

Another striking early response came to the TAPIA invitation for writing “pointedly about the here and now” followed the PNM celebration of Eric Williams’ hot new book, “From Columbus to Castro”. In a devastating critique, titled “History as Absurdity”, that ran over two issues, UWI lecturer Gordon Rohlehr noted the “fantastic claims” made by Dr Williams and the campaign “to use the publication as a means of bolstering up his political position in T&T”. Dr Rohlehr concluded about the historian Prime Minister: “He must have been living in a hermit’s cell somewhere.” A shorter version of the From Columbus to Castro review had earlier been offered to the Express. Its editor said No thanks. “History as Absurdity” was in 1974 published internationally as a chapter in the Doubleday book, “Is Massa Day Dead?” Dr Rohlehr continued to be a TAPIA contributor of magisterial dimensions on literary subjects.

As an outlet for literary criticism, and also literary output, TAPIA so established itself as to attract writings, among others, by Lloyd King, Victor Questel, Earl Augustus, Christopher Laird, Wayne Brown, Merle Hodge and Derek Walcott. The open-house posture was maintained for in-depth writing on topics such as Caribbean history a subject covered by Fitz Baptiste, and T&T architecture by Brian Lewis, JS Kenny on the environment, Anselm London on economics, Baldwin Mootoo on cricket, among other bylines on other topics.

Meanwhile, a team of insiders rallied to the cause of filling TAPIA pages, beyond the capacity of the nucleus of hired hands. The overarching obligations of the Tapia House political focus kept being met by a widening cohort of activist members who doubled as community action reporters such as Ivan Laughlin, Lloyd Taylor, Ernest Massiah, Michael Harris, Mickey Matthews, Jerry Pierre, Ronnie Grant, Ruthven Baptiste and Earl Best. Alongside, in what was called the “hardwuk”, an identifiable corps was recruited from the mainstream media. In effect, big names such as Keith Smith and Raoul Pantin showed up as TAPIA bylines.

Another source, in the heyday that lasted through 1973, comprised student-adherents to the Tapia St Augustine branch. In this category stand-out names included Dennis Pantin, Esther Le Gendre, Pat Downes. Editorials and, for the most part, front pages remained the province of ranking Tapia politicos, starting with Lloyd Best.

Somehow, also, TAPIA remained a singular source of research data on current affairs. Memorable among these, with resonances today, is the 12-month 1973 listing of people and police officers killed and wounded in anti-crime and anti-guerrilla operations. In 1971, an “age ladder” of in-the-news political figures put Eric Williams at the top (age 60) and Dave Darbeau and the bottom (age 24). Other helpful listings showed the annual rise by percentage in basic foods; strikes over a one-year period; and the shring value over five years of the TT dollar.

Looking back, in some longing, produces memories of TAPIA coverage of Carnival, pan, calypso, community strivings, labour unrest, and race relations. Keith Smith reported on the walk-out by Indian students from a calypso contest in which one contestant, costumed in capra and dhoti, performed as non-Indian students jeered the walk-out. An accompanying photo captured graffiti on the UWI wall: “Indians and Africans Unite…Fake”.

For as long, it seems, as the Tapia politics held promise, the TAPIA paper followed suit. Once Tapia was put to the political test, and failed, however, the TAPIA paper needed to seek another reason for being. In vain as it turned out.

Front page lead headlines:

Issue Number 1: “The Coming Election” Lloyd Best 28 September 1969

Issue Number 2: “University Boiling Pot” Lloyd Best

Issue Number 3: “Whose Republic?” Lloyd Best

Issue Number 4: “Confidence Trick—How Williams Pulled Off the Budget Debate”

Issue Number 5: “Plenty Parties, Plenty Balls” Adrian Espinet

Issue Number 6: “Steal Mill—Any Price” Emile Elias

Issue Number 7: “The Mixture As Before—Williams TV Address” Denis Solomon

Issue Number 8: “Mr Smith’s Ship Sink” Lloyd Best

Issue Number 9: “POWER TO THE PEOPLE”

Issue Number 10: “NO ELECTION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION”

Issue Number 11: “ELECTION? WHAT TO DO”

Issue Number 12: ’70—YEAR OF REVOLUTION”

Issue Number 13: “BUT WHO WE GO PUT?”

Issue Number 14: “PRICE OF INJUSTICE—$1,068,500”

Issue Number 15: “NATIONAL CRISIS” (collage of headlines)

Issue Number 16: “GOD HELP OUR GRACIOUS KING…!”

Issue Number 17: “THE BETTER TO BRAMBLE YOU WITH MY DEAR”

Issue Number 18: “THE PEOPLE MUST TALK”

Issue Number 19: “IN THE NAME OF THE DOCTOR” Merle Hodge

Issue Number 20: “INDEPENDENCE FOR KEEPS”

Issue Number 21: “THE CHEESE STANDS ALONE”

Issue Number 22: “NOT BLACK POWER BUT BLACK GOLD”

Issue Number 23: “BUMPER TO BUMPER—WOES OF THE TAXIMAN” Lloyd Taylor

Issue Number 24: “WELL, WE ENT FRAID KARL”

Issue Number 25: “LET US BLOCK THIS POLICE STATE” 02 APRIL 1972